Source: https://sites.google.com/site/spritetump/odobrosonha

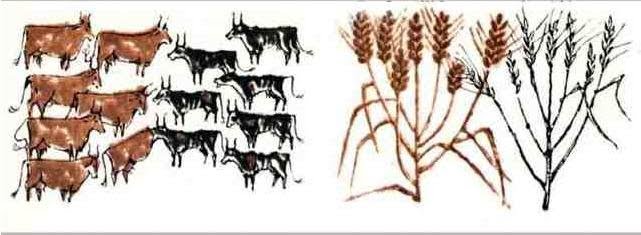

25 Then Joseph said to Pharaoh, “The dreams of Pharaoh are one; God has revealed to Pharaoh what he is about to do. 26 The seven good cows are seven years, and the seven good ears are seven years; the dreams are one. 27 The seven lean and ugly cows that came up after them are seven years, and the seven empty ears blighted by the east wind are also seven years of famine. [Genesis]

Businesses are about people. People who do, people who lead, and people who count stuff. This is about the counters. The bean counters. The dour professionals with their ledgers and their double entries. With their standards and their prudence. The accountants.

There are two distinct classes of accountant. The first win their spurs in the rarefied atmosphere of a professional services firm. They’re not the cream of their graduating class. Those guys and girls got snapped up by the boutique consultancies. They’re not the most ambitious, that group goes on to endure sixteen-hour days, bullying and bigotry in an investment bank. No, the ones who file through the doors of the big four accountancy firms to join the training treadmill are good but not great, maybe (whisper it) just a bit boring. Or shout: Pasty faced shoegazers.

Of those the really wild ones, the ones that wear brown shoes, go into tax.

A notch further down this hierarchy go to the second-tier firms, let’s not worry about them.

And then you have the waifs and strays of the finance profession. The urchins, urchin’ around on corporate graduate schemes to become what no parent wishes for – a management accountant. I was one of those, out of university without a clue and onto the only graduate scheme that was still hiring. I became an accountant by mistake, and it took me sixteen years to stop.

There is a whiff around accountants these days. It is not as bad as the miasma surrounding bankers, who are the unwholesome spawn of Baal, but a sulphurous odour nonetheless. The failure of Carillion is a recent but not isolated lodestone for public ire.

Carillion, and all such failures, are first and foremost the failure of their own management team, but attention inevitably turns to their auditors. Where were the standards and the prudence while the company flushed its way down the toilet?

My answer lies with the Prophet Joseph and God.

Text books are filled with all the worthy roles a finance function performs to keep its host business alive and healthy. I doubt any of them mention that it plays the role of Joseph.

Being employed is as much about the certainty of employment next year as it is about this week’s wages (unless you are one of the sociopaths known as an entrepreneur). That gives the internal accountant or the commercial finance person or management accountant, call them what you will, two key but rarely mentioned tasks: dealing with lies and making life boring.

People will lie for an easy life. Whether it is the operational manager whose team could not possibly deliver cost savings next year, or the salesperson bemoaning market conditions for a lower revenue target, the life of the management accountant is beset by liars. Learning the business, filtering out the bullshit and being credible in this environment is a core skill which means you can put together a coherent, challenging and achievable business plan.

Making life boring is just as important. Steady, predictable growth and modest improvements year on year keep everyone employed. Bonuses don’t fluctuate, hard questions are avoided.

Life and business aren’t like that. Myriad exogenous factors can lead to a good year or a bad year. In this the CEO is pharaoh, the management accountant is Joseph, and the granaries are the balance sheet.

Putting a little bit aside in a good year is just prudence. A provision against what may befall in the future: I may owe someone money in the future, I’ve assessed the risk, I’ve taken a little bit out of this year’s profits against that possibility.

Often this is for a good, uncontroversial reason, a regulatory fine under appeal perhaps (Grant Thornton have some recent experience with that). Sometimes it is just because this year’s numbers are looking a bit too good, and next year might be tough. Smoothing out volatility makes everyone more comfortable, and in the medium term all profits will be declared, all taxes paid, and no harm done. A victimless crime. In fact, in the exercise of judgement and prudence, not a crime at all.

Everyone sleeps well at night.

Where is the auditor in all of this? In practical terms – utterly powerless. As a financial controller I expected my junior finance managers (around their first full year post qualification) to be able to run rings around any auditor. We ran the numbers for big business divisions, billions in annual revenue. My FMs could justify a provision one day, and when head office said the consolidated numbers looked a bit better the next day, argue the opposite. Sometimes they did this just to alleviate the grind of the year-end close.

Learning to deal with liars makes you quick on your feet and fills your armoury with credible half-truths and myths about the business. I’ve made up this example to protect ex-colleagues, but they’ll recognise the tone “we get more refund claims against us on a Tuesday, and next year there are more Tuesdays than this year, so some of the revenue earned this year is at risk…”

You can’t really blame the auditors. It is a profession populated by the mediocre middle classes and a rare few clawing their way up the class ladder. Most have never stepped outside the glass and steel edifice of their employer and done an actual job with a business that makes things. As their careers progress the cream keep getting skimmed off to do business advisory work or are enticed away by corporate riches. Quality diminishes with seniority.

In which case what is the point of the tax every business has to pay in audit fees?

And so we come to God. People behave better when they think there is someone watching. A warning sign about speed cameras makes you slow down, even if you are pretty sure there is no actual camera.

Most accounting is carried out by software, most decisions, even marginal ones, are benign. The presence of the auditor is just to remind the CFO not to do something really bad. The probability that Tina or Tim nice-but-dim from DeToiletWaterhouse will actually catch you is low, but the consequences are high, so don’t do it.

That’s fine when good years are followed by bad years and more good years. But think about Joseph. What happens in the eighth year of famine? At that point the Prophet could no longer rely on his prudence and draw on the granaries. He’d need a miracle.

Accountants can perform miracles too. Balance sheet sleight of hand and some fast talking can draw forward future performance and prop up the eighth year. Sometimes they get away with it, the ninth year is fine, the borrowed future repaid, and everyone sleeps soundly again. Employees keep getting paid, audit fees are earned and disaster avoided. Another victimless crime?

Maybe.

No one knows with certainty what will happen in the ninth year. And at what point does Pharaoh (the CEO) who has put years into a business, or a deposit on a yacht, have the incentive to say “actually, we’re toast.”

Aha, but God (aka the auditor) is watching.

True. But remember all those little white lies, the marginal provisions? We all know there is no camera, and anyway the auditor might be so monumentally incompetent as to miss red flags for years (back with Grant Thornton).

Besides, if by some quirk of fate the auditor is competent, s/he isalso invested in the business. Years of boozy lunches and advisory add-ons have been earned. Believing in the ninth year means they may be earned again. The auditor that calls foul in the eighth year is a heretic. Any business can have a run of bad luck, who wants an auditor that does not believe?

The myth is that oversight works. Thousands of years of religion have proved this to be untrue. Paradise is a long way off; the pleasures of sinning are present and immediate. God may be watching, but most of the time (floods and plagues of locusts aside) does nothing. And auditors are far from omniscient.

Just like everyone else they also want to be employed next year. Except on the very brink of disaster, there is no incentive for them to call out a business that is sinking.

The entire system needs a rethink. It is grounded in a history of manual ledgers and petty cash. The risky parts of the economy are now wholly electronically controlled. Money is digital, transactions are coded. It is possible to be omniscient about transactions. The risks are all in the making of decisions. Why force every business to pay the audit fee tax, the modern day tithe to the church, for oversight that is over-engineered and yet impotent?

Better in my view is a system which focusses where the risks are. A smaller, better experienced, commercially aware and technically well-resourced group that can spot check businesses at will. An arm of government that is protected from mixed incentives, with tools and powers to keep businesses on their toes. Like the SFO but better resourced and frankly, cooler.

END

The views expressed are strictly my own and not those of any employer past or present.

This post was lightly edited and updated in Sept 2021.

Find out more about my writing here.

Very interesting reading, thank you.

LikeLike